The Short Loin and Other Myths

How often have you heard it? "The Lhasa should have

a long

body

and

a short loin". "A long loin is not good as it is

weak." "A

short loin is strong". And the good word associated with

"back"

is

"short". The bad word is "long". Where did all of

this come

from? Certainly not from the standard which in all cases

throughout

the world asks for a rectangular outline - "longer than

tall".

And

no Apso standard in the world asks for a short loin. No

standard

even defines where the loin is. So in this article we will

attempt

to answer 4 questions:

1. Where exactly is the

loin, and how

does one measure it?

2. What determines loin

length?

3. If it should be "short", why?

4. If it should be long, why?

I would

like to lay a bit of anatomical foundation for the

discussion.

The axial skeleton of the dog consists of a skull, 7 cervical (neck)

vertebrae,

13 thoracic vertebrae, each one carrying an attached rib, 7 loin

vertebrae,

the sacrum and the tail with a variable number of vertebrae - up to 26.

The flexibility of the torso is mainly

confined to the

loin.

Why? The torso consists of the thoracic vertebrae and their attached

ribs,

and the loin and sacrum. There is no mobility in the sacrum

which

consists of 3 fused vertebrae. Likewise the chest

cavity is a

more or less rigid box containing the heart and lungs.

The first 9 ribs are attached fairly rigidly to the

sternum.

There

can be very little flexion or extension at all in this segment. The

next

three ribs are connected at their terminal ends to a rubbery piece of

cartilage

which then connects to the sternum. Very little freedom of

movement

there either. The last, 13th, rib is floating and not

connected

except

by muscles to the 12th rib. In addition to the bony and

cartilaginous

attachment of the ribs, they are also connected to each other by strong

bands of muscle which can contract to narrow the chest cavity

laterally,

or relax to expand it. These muscles also limit the flexion

and

extension

of the spine.

What we are left with, to the rear

of the rigid protective box of

ribs

and thoracic spine, is the loin - 7 vertebrae which are free

to move

in dorsal flexion and extension, lateral flexion, and

twisting

motions

as well.

Well, what is the loin and what is it

that some people erroneously

call

the loin? The loin is the chunk of lumbar spine and

paraspinal

muscles as

indicated in the attached diagram. The loin is 7 vertebrae

long.

The entire spine from the top of the scapular spine (at the 2nd

thoracic

spinal process) to the sacrum is 19 vertebrae long. The

lumbar

vertebrae

are larger than the thoracics, so that the loin comprises approximately

45% 0f the length of the back from wither to pelvis. The only

anatomically

correct way to measure the loin is along the spine, not on the sides of

the dog.

Some

have stated that the loin is the area from the last rib to

the

wings

of the pelvis. Again, this is not the loin.

the loin is

the area from the 13th thoracic vertebra to the first sacral vertebra.

It is a segment of the spine consisting of the 7 lumbar vertebrae and

their

associated attached muscles. It is the same part of the dog

that

when taken from a hog, you buy as "loin of pork". What they

are

describing

may be termed the flank, but it cannot be termed the loin, because that

term already has an anatomical definition upon which canine anatomists

and hog butchers agree. That name is already taken - and has

been

so for hundreds of years.

Some

have stated that the loin is the area from the last rib to

the

wings

of the pelvis. Again, this is not the loin.

the loin is

the area from the 13th thoracic vertebra to the first sacral vertebra.

It is a segment of the spine consisting of the 7 lumbar vertebrae and

their

associated attached muscles. It is the same part of the dog

that

when taken from a hog, you buy as "loin of pork". What they

are

describing

may be termed the flank, but it cannot be termed the loin, because that

term already has an anatomical definition upon which canine anatomists

and hog butchers agree. That name is already taken - and has

been

so for hundreds of years.

Some have described the

loin as anything from 1 to 3.5

inches.

My question to you is - should a rather long-bodied mountain

dog be

rigidly or flexibly coupled? If you say rigidly,

then you are

describing the short, rigidly coupled fox terrier type of

body.

Some

breeders have evidently been trying to change the apso to that style of

body for years, but IMHO that is not an Apso.

If

you say flexible, then I want to know how much flexion do you

think

a dog with a 1 inch loin could have? Or even a 1 inch flank?

(since

that seems to be the anatomical area that everyone has been referring

to

as the loin.)

The

flank length will vary with the length and angle of the last two ribs. The

loin is ALWAYS proportional to the length of the rest of the spine.

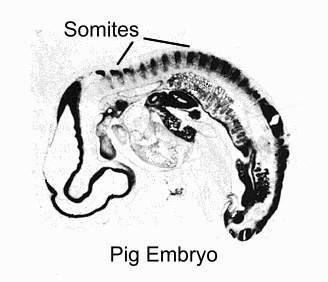

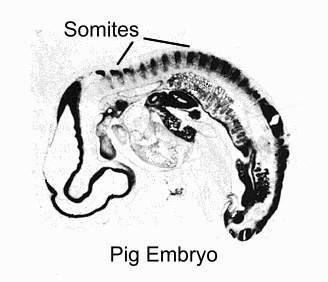

Embryologically, the spine forms as one tube which then segments into

the

vertebrae and associated muscles. These early segments are

called

somites. See figure attached. There is no way to breed a dog

to

have

long thoracic vertebrae and short lumbar vertebrae.

Therefore, if

you have a rectangular dog (longer than tall) it will have a relatively

long loin as well. God made the rules - I didn't.

The

flank length will vary with the length and angle of the last two ribs. The

loin is ALWAYS proportional to the length of the rest of the spine.

Embryologically, the spine forms as one tube which then segments into

the

vertebrae and associated muscles. These early segments are

called

somites. See figure attached. There is no way to breed a dog

to

have

long thoracic vertebrae and short lumbar vertebrae.

Therefore, if

you have a rectangular dog (longer than tall) it will have a relatively

long loin as well. God made the rules - I didn't.

Furthermore, a very short loin would interfere with

flexibility.

A long stiff dog would not be agile. If the ribs

are too

close

to the pelvis, the thoracic cage impinges on the pelvis on turning and

flexing the body. - Like a short-waisted human figure.

Finally, where does it say, in any standard, that

the loin

should

be short? Where oh where did this myth arise? I

think I know

- the same place the "short back" cult came from. To its

credit,

the Canadian standard says, "LOIN: too long a loin adds excess length

to

the back and results in a loss of strength to the forepart of the body.

If the loin is too short there will be a loss of

flexibility."

While

there is some question as to length causing a loss of strength, the

latter

part of this sentence is very obviously true.

Just

grabbing the dog at the waist and estimating the

distance

between the end of the ribcage and the muscle of the upper thigh may

give

you a rough estimate of the length of the flank, but it is not

a

"measurement"

of the loin length. Please refer again to the

textbook

illustration

of how to measure the loin, and read the accompanying legend.

The

loin IS the 7 lumbar or loin vertebrae, easily measured by

counting

to 7 forward along the spine beginning with the easily palpable last

lumbar,

just in front of the pelvis. Since this involves measuring

easily

palpated BONY landmarks, it is accurate as well. It is

extremely

easy to feel the first and last lumbar vertebrae. The shape

of

the

spines is different from the thoracics and the sacrals. Where

even

the slightest lateral curvature of the spine can throw a measurement of

the flank way off, the midline measurement is always the same,

and

there is minimal possible error.

We

might ask "what is the point anyway"? The standard

makes specific

reference to the body height and length based on precise landmarks.

Some

standards give a measurement of the nose length as well. Since no

standard

even mentions a measurement of the loin, measuring it may not be worth

the trouble. My mother always said "If it is not worth doing right,

then

it is not worth doing at all!" I think she may be on target

in

this

case. Since the apso standard does not request a particular length of

loin,

my only interest in the loin is to see if it is strong - as the

standard

states it should be. But if for some reason someone wants to

measure

the loin, there is only one way to do it - the right way.

Can

grabbing the waist be useful in telling whether a dog is "well

ribbed

up"? Yes I suppose so. The length of the flank may

give

some

indication of the slant and length of the last few ribs, ("well ribbed

up" implies relatively long terminal ribs) but that can better be

estimated

by palpating the ribs themselves..

I

think that the "short loin" cult, like the "short back" cult

is

something which has crept into our notions of the breed, even

though

it exists nowhere in any standard, and is even refuted in the earliest

standards:

"Body.

There is a tendency in England to look

for

a level top and a short back. All the best specimens have a slight arch

at the loin and the back should not be too short; it should be

considerably

longer than the height at the withers. The dog should be well ribbed

up,

with a strong loin and well developed quarters and thighs." - Lionel

Jacob,

1901

Notice that Mr. Jacob describes the loin correctly as the keystone arch

of the lumbar spine. There is no implication here of a short

back

or loin as being correct. He wants strength in the loin, and good

development

of the hind quarter. The idea that weakness is synonymous with length

is

erroneous. Long and thin might be weak, as would short and thin, but

long

and well developed may, for good reasons, be stronger than short.

There

are good anatomical reasons for wanting good sized lumbar

vertebrae,

with resultant length of loin. The loin musculature is what

provides

the coupling for the rear drive. The powerful muscles which

originate

on the lumbar vertebrae and last rib and insert on the pelvis are the

rearing

muscles - the psoas major and minor and the quadratus lumbricalis,

assisted

by the longissimus dorsi and the strong fascia of that

muscle.

The

amount of muscle in the loin will depend on the surface area upon which

the muscle originates. Less length and width of the

vertebra,

the less muscle you can have. So it does not follow

that

length

= weakness. THIS IS A MYTH.

This is what McDowell

Lyons has to say about the loin:

"

Between the thoracic section and the pelvis or

croup,

we have the loins, consisting of seven vertebrae. These are

longer

and wider than the dorsal (thoracic) vertebrae and their spinous

processes

are short, thin and wide, being inclined forward to give better support

to the action of the dorsal or rearing muscles in this

vicinity.

This section does not receive support from the other bones in the

framework

but sets like a bridge or arch between the two business ends. ... The

keystone

arch should be sought in all breeds for the loin section, but generally

this should not be greater than necessary to provide structural

support.

If there is to be a deviation, let it be upward into a roach for those

will not sag and become soft as quickly as a loin

without any

arch."

How many Lhasas do we see (even the very short backed ones) with tipped

up pelves and sagging loins? Everyone seems to fault a slight

roach

in the topline, and overlook the truly unsound sagging loin.

In

the

quest for the mythologic short loin, we can breed for miniaturization

of

the vertebrae - and some breeders may have accomplished this.

With it

they have achieved sway backs, with weak and unstable musculature. Is

this

healthy? Is this what a mountain dog needs to survive?

In

summary: We have found out where the loin actually

is

and how to measure it. A short loin on a long dog

is an

anatomic

oxymoron. Nature does not manufacture the spine in

pieces -

either

all the vertebrae are short, or they are all long. The length

of

the flank depends on the length of the loin and the length and angle of

the last few ribs. A well developed strong loin IS called for in every

standard of the Lhasa Apso. The size of the

vertebrae (length

and width) determines the amount of musculature of the loin.

It follows that small, foreshortened vertebrae will result in a weak

loin,

rather than a strong one.

So is there any merit

to attemping to "measure" the loin?

the

standard does not even mention it, so my answer is: If you want to

measure

it, do it right, otherwise measuring by cruder means is irrelevant. The

length of the loin will always be in a fixed ratio to the length of the

entire spine, so why bother? If the dog is well balanced with a broad, muscular, slightly arched loin, the loin

length is correct.

Some

have stated that the loin is the area from the last rib to

the

wings

of the pelvis. Again, this is not the loin.

the loin is

the area from the 13th thoracic vertebra to the first sacral vertebra.

It is a segment of the spine consisting of the 7 lumbar vertebrae and

their

associated attached muscles. It is the same part of the dog

that

when taken from a hog, you buy as "loin of pork". What they

are

describing

may be termed the flank, but it cannot be termed the loin, because that

term already has an anatomical definition upon which canine anatomists

and hog butchers agree. That name is already taken - and has

been

so for hundreds of years.

Some

have stated that the loin is the area from the last rib to

the

wings

of the pelvis. Again, this is not the loin.

the loin is

the area from the 13th thoracic vertebra to the first sacral vertebra.

It is a segment of the spine consisting of the 7 lumbar vertebrae and

their

associated attached muscles. It is the same part of the dog

that

when taken from a hog, you buy as "loin of pork". What they

are

describing

may be termed the flank, but it cannot be termed the loin, because that

term already has an anatomical definition upon which canine anatomists

and hog butchers agree. That name is already taken - and has

been

so for hundreds of years.  The

flank length will vary with the length and angle of the last two ribs. The

loin is ALWAYS proportional to the length of the rest of the spine.

Embryologically, the spine forms as one tube which then segments into

the

vertebrae and associated muscles. These early segments are

called

somites. See figure attached. There is no way to breed a dog

to

have

long thoracic vertebrae and short lumbar vertebrae.

Therefore, if

you have a rectangular dog (longer than tall) it will have a relatively

long loin as well. God made the rules - I didn't.

The

flank length will vary with the length and angle of the last two ribs. The

loin is ALWAYS proportional to the length of the rest of the spine.

Embryologically, the spine forms as one tube which then segments into

the

vertebrae and associated muscles. These early segments are

called

somites. See figure attached. There is no way to breed a dog

to

have

long thoracic vertebrae and short lumbar vertebrae.

Therefore, if

you have a rectangular dog (longer than tall) it will have a relatively

long loin as well. God made the rules - I didn't.